Shanghai Taoists showing respect to gods with incense.

Shanghai Taoists showing respect to gods with incense.The Center of Traditional Taoist Studies teaches classical Taoist theology based on a holistic view of the universe with religious tenets underlying a system of practical concepts. Whereas Western philosophies and religions have generally viewed reason and faith as mutually exclusive, classical Taoism integrates the two. This is a consequence of recognizing that the forces of the Tao act upon the heavens as well as the earth, making the two indivisibly coupled and thus clarifying, not complicating, understanding. Such a grounded attitude can be traced to Taoism's shamanistic origins with religious practices born of a time when concrete goals were essential amongst simple peoples trying to survive in a harsh environment.

Taoism's religious practices build a bridge between one's earthly human form and the heavens. In the quest for oneness with the universe, Taoists work to understand their paths — which ultimately lead to the Great Ultimate. Prayer, as performed at the Center, opens a two-way communication channel to the heavens. In this way, a devout Taoist sends an appropriate message to the Great Ultimate and receives a concrete answer in return; guidance from the Heavens augment spiritual instruction to clarify one's path.

To the classical Taoist, life is an on-going effort to unscramble the confusions of the soul. Taoist philosophy provides principles to live by, and guidance from the gods helps see reality more clearly. This not only yields a better daily life, but also points to Taoism's purpose of life: our soul is placed on earth for a short time to better tune itself to mortal reality. If successful, when the body is cast off, the surviving entity, the soul, is more likely to be accepted by the Great Ultimate. Thus, the duality of existence means that a better life on earth provides for a better afterlife. Significantly, there is no required sacrifice of one for the other, the two existences are complimentary and inextricably bound.

Pantheon of Gods

While the Center of Traditional Taoist Studies teaches the grounded applications of physical Chi Quong and meditation, it is important to understand that the temple is first and foremost a holy place, the Temple of Original Simplicity. If a congregation member wished to only improve his physique, he should go to a health club; if he only wished to only learn philosophy, he should go to college. The core of the temple is the religion of the Tao. Accordingly religion permeates all that is taught... it can't be separated out.

The Temple's congregation performing traditional Taoist ceremony.

The Temple's congregation performing traditional Taoist ceremony.Spread throughout the temple are religious icons that serve as reminders of Taoism's core principles. For example, the yin-yang symbol is frequently displayed to remind students that duality binds all natural phenomena: light with dark, action with inaction, and life with death. Similarly, swords and weapons throughout the temple remind all visitors that life is a struggle, a fundamental premise underlying Taoism's prescription to successfully deal with daily challenges.

Most prominent, however, are images of Taoist gods, representing a specific principle or an important life lesson. The God of Health, for example, reminds the congregation of the importance of maintaining the physical body, the house of the soul.

God of Health and Longevity

God of Health and LongevityIt is the duty of the Temple of Original Simplicity's master, Grand Master Anatole, to invite appropriate spirits to inhabit these images using ancient "eye opening" ceremonies -- the Taoist equivalent of consecration. Once activated, they serve as the communication portals by which the congregation can pray for celestial guidance. In a sense they become personal oracles to devout Taoists.

Traditional Taoist theory holds that the spirits represented via the temple's images are celestial beings that have achieved their position in one of three ways. Consistent with Taoism's martial theme, the first category of spirits is that of mortal heroes who died a violent death. Similar to Christian "saints," these spirits protect those Taoists who sincerely communicate with the heavens and try to live spiritual lives. In this sense, Taoists earn the right to be "chosen people" favored by the heavens, unlike other faiths whereby such status is a birthright or simply self-selection.

God of War

God of War God of Magical Power

God of Magical PowerThere are literally hundreds of Taoist spirits, organized according to a strict hierarchical system with their consecrated images appropriately arranged throughout the temple. While each master has some limited freedom to accentuate certain deities, there remains a specific layout that is consistent across all classical temples; one adhered to by the Center's Temple of Original Simplicity.

Fox Creed

Taoist temples, regardless of location, tend to honor a consistent set of gods, including the Three Pure Ones, Star Gods, God of War, and so on. In addition, many temples emphasize certain deities according to their individual traditions or beliefs. The Center's Temple of Original Simplicity actively embraces the Fox Creed, an ancient practice of worshiping spirits known as "Inari." While Inari spirits can manifest in a variety of forms, it is the fox form that the Temple honors.

Ancient Fox altar in Japan

Ancient Fox altar in JapanThe Creed of Foxes has mysterious origins, beginning in China/Mongolia 3000-4000 years ago when peasants noticed that the presence of foxes often coincided with healthy crops and other good fortune. Thus, fox altars were built to attract good luck and a complex belief system evolved over several millennia as shaman priests explored their metaphysical aspects. Over time, the Fox Creed grew more secretive in China, only to be practiced by elite Taoist clergy; however, after migrating to Japan in the 8th century, became immensely popular throughout Japanese culture and today there are over 32,000 fox shrines in Shinto temples throughout the country.

It is the unique animal qualities of foxes that importantly contribute to the Taoist understanding of their connection to the spirit world. Significantly, the fox is elusive with generally mysterious behaviors. Unlike wolves, foxes cannot be domesticated, living according to their own rules and not abiding by convention. The common expression, "Sly as a fox," is representative of this wily characteristic.

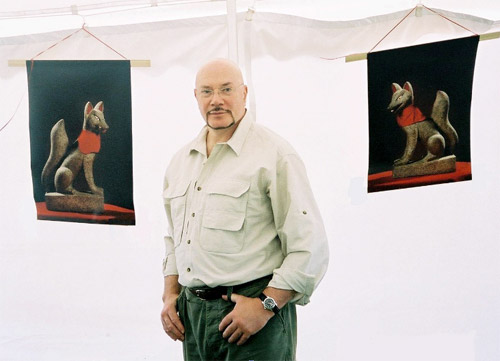

Grand Master Anatole at gate of the Inari Fox Temple in Kyoto, Japan. Note fox statues on either side of entrance.

Grand Master Anatole at gate of the Inari Fox Temple in Kyoto, Japan. Note fox statues on either side of entrance. Fox Altar at Temple of Original Simplicity

Fox Altar at Temple of Original SimplicityBecause the fox burrows underground, it is thought, like snakes, to possess the wisdom of underlying or fundamental principles. And this profound knowledge, combined with the foxes' unconventional qualities, is indicative of its unique abilities within the metaphysical world. In this case, fox spirits were discovered by shaman priests to be able to "fold" time and space, violating the commonly held model of physical reality. So while the Western world was discovering the world wasn't flat, Taoist masters were using fox spirits as pathfinders across dimensions. For a select group of shaman priests, fox spirits became a working bridge between the physical and nonphysical worlds.

There are many conventions associated with the Creed of Foxes, but one of the most interesting relates to their depiction on altars. Classically, foxes are displayed in stylized statues of male and female pairings; the male is on the left with a parchment (or key) in its mouth and, on the right, a female with a pill in her mouth. The parchment represents sacred knowledge, whereas the pill is a "seed" that can produce an immortal soul. For acolytes devoted to the Fox Creed this implies both a transcendental benefit, but also a serious obligation: sacred knowledge acquired by crossing time and space (represented by the parchment) can nurture the soul (the pill). However, to squander or misuse such a gift carries grave consequences. The Temple of Original Simplicity adheres to original Inari practices, long thought lost to the modern world.

Grand Master Alex Anatole and his disciple Master Richard Percuoco conduct a seminar about "The Creed of the Celestial Foxes"

Grand Master Alex Anatole and his disciple Master Richard Percuoco conduct a seminar about "The Creed of the Celestial Foxes"

Astrology

Classical Taoist theory identifies three realms to describe the influence of universal forces upon mankind: the heavens, man in the middle, and the earth below. Man, situated between the two, is a conductor of life-energy (sometimes called "Chi") between heaven and earth. All Taoist sciences, from Chi Quong to acupuncture to meditation, are built upon this principle, which forms the basis for Shamanistic and Taoist religious practices. Operating within this paradigm, Taoist astrology is used as a systemization of the heavenly forces above man, and minerals and animals for the earthly forces below man. These fundamental tools, used by Taoist priests, codify the two realms that bracket man and affect his fate.

While Taoist astrology describes how the forces of the heavens manifest their action upon mankind, the earthly dimension of universal energy exerts equally powerful effects. And the combination of these forces either increases or decreases an individual's animal power. Animal power reflects the corporeal aspect of existence that, if weakened, makes one vulnerable to physical hardship and disease. Taoist priests perform astrological calculations and then adjust them to factor in the effects of earth's natural cycles through the use of specific minerals (e.g. quartz and malachite), herbs, and other techniques. They use these procedures to invite the appropriate missing animal power back into the weakened individual, thus restoring balance. The master can also use the power of certain animals to serve as liaisons between guardian spirits and the individual.

According to classical Taoism, each person is born under astrological signs representing a specific configuration of stars. Thus, every individual possesses his own "frequency," which is associated with inherent Chi energy determined by the star configuration at the time of birth. These celestial alignments serve as channels of the cosmic energy beamed to each person; changing this "beam pattern" affects one's fate. Thus, the priest's objective is to realign an individual's personal Chi with that of the Cosmos, as dictated by astronomical configurations. This technique corrects ill fate that results from "misalignment" caused by internal mental confusion or external metaphysical forces.

The 60 Zodiac Gods at Shanghai's White Cloud Temple reflect Taoism's 60-year astrological cycle.

The 60 Zodiac Gods at Shanghai's White Cloud Temple reflect Taoism's 60-year astrological cycle.Using the sacred knowledge bestowed by masters from several millennia ago, corrective "realignment" is accomplished using prayer, rituals, ceremonies and talismans. For convenience in the calculation process, ancient Taoists developed a system classifying these frequencies into groups of animals, trees and stones. Augmenting this manipulation is a sphere of life-energy radiating from a powerful Shaman or Taoist master, favorably affecting the fate of those within the temple.

Magic Diagrams

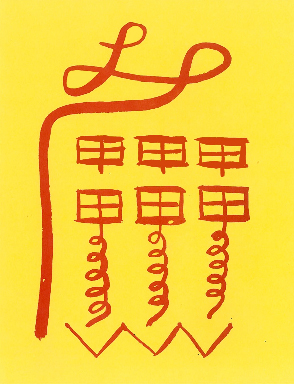

A Taoist diagram for success.

A Taoist diagram for success.Taoist "magic" diagrams date to the origins of Shamanism and have been used for several thousand years. Given their Shamanistic heritage, magic diagrams were originally drawn with wooden sticks in the sand of special "sandboxes" or on the banks of rivers using reeds. Over time, these drawings were inscribed on the bark of trees and finally upon specially produced scrolls. In their final, most powerful form, magic diagrams were painted with red brush strokes on yellow or gold paper.

How do these powerful diagrams work? All of Taoism's practical applications are based upon the manipulation of unseen energy called "chi." In martial arts and holistic healing, chi manipulation yields tangible results that can be witnessed in dramatic physical ways. In a similar sense, Taoist diagrams harness the power of cosmic chi.

A Taoist diagram for protection from malevolent forces.

A Taoist diagram for protection from malevolent forces.Taoist alchemists discovered that brush strokes conforming to specific configurations could modify a person's aura (or individual chi) when made by a powerful Master. This procedure captures universal or cosmic chi from its normally disperse state and concentrates it. In a unique conjunction of mathematics and art, the configuration of the diagram contains encoded "information" that creates a specialized receptacle for the captured cosmic chi according to its specific purpose. In this way, the diagram can change an individual's chi flowing throughout his meridian system and reconnect him to the beneficial flow of the Universe. Diagrams are hung throughout the Temple of Original Simplicity and used in its meditation and ceremonial programs.

View virtual tour of the "Pantheon of the Gods"

View virtual tour of the "Pantheon of the Gods" View virtual tour of the Temple of Original Simplicity

View virtual tour of the Temple of Original Simplicity next

next top

top